CVS and Subversion vs. VSS/SourceSafe

Here's a response I gave to a fellow on an email list I'm on yesterday. He was having trouble understanding that CVS (and other source control systems) didn't "lock" files (checkout with reservation) as he has been a VSS person for his whole career. This is what I said (a bit is oversimplified, but the essense is there):

With VSS you:

Checkout with reservations – meaning that developer has an exclusive lock on that file.

With CVS you:

Edit and Merge optimistically – developers can make a change to any file any time. However, CVS is the authoritative source and they must Update and Commit their changes to the repository.

It sounds scary, but it’s HIGHLY productive and very powerful. It works more often than not, as most devs don’t work on the exact same function. It is largely this concept that makes Continuous Integration work.

It’s a FANTASTICALLY powerful way to manage source. No need to wait for that “locked” file. Source files can be edited at any time. For example, if there is a file with two functions:

Line1: Public void a()

Line2: {}

Line3:

Line4: Public void b()

Line5: {}

Two developers can edit the same file, different functions:

Line1: Public void aChanged() <- DEV1

Line2: {}

Line3:

Line4: Public void bDifferent() <- DEV2

Line5: {}

These changes are called “non-conflicting.” CVS will automatically merge them. Now, we don’t know if they files will still compile (that’s the job of the developer and the build system) but since different lines of text are changed, they don’t conflict.

If two devs change the SAME LINE, then CVS holds both changes with “Conflict Markers” and demands that the developer RECONCILE the changes before committing. I manage all the dasBlog development worldwide using CVS. How could I do that if I allowed you in India to LOCK a file for days at a time? For example, when you are done working in your sandbox, it’s your responsibility to merge your changes in with the mainline.

From http://www.atpm.com/7.03/voodoo-personal.shtml

"CVS (Concurrent Versions System) is an open-source version control tool that’s extremely popular in the Unix/Linux world. CVS is a client-server system, which makes it easy for multiple users, possbly scattered across the Internet, to collaborate.. In fact, Apple uses it internally to manage the development of Mac OS X, and to make their sources for the Darwin kernel available to the world. CVS’s signature feature is its use of “optimistic” locking to let multiple people work on the same file at the same time. It then automatically merges their changes and signals whether it thinks human intervention will be required to complete the merge. (It seems like it would take magic for CVS to do this reliably, but in practice it has worked very well for me.) CVS (Concurrent Versions System) is an open-source version control tool that’s extremely popular in the Unix/Linux world. Unlike Projector and VOODOO Personal, CVS is a client-server system, which makes it easy for multiple users, possibly scattered across the Internet, to collaborate. Although only the client runs on Classic Mac OS and Windows, the server runs on Mac OS X. In fact, Apple uses it internally to manage the development of Mac OS X, and to make their sources for the Darwin kernel available to the world. CVS’s signature feature is its use of "optimistic" locking to let multiple people work on the same file at the same time. It then automatically merges their changes and signals whether it thinks human intervention will be required to complete the merge. (It seems like it would take magic for CVS to do this reliably, but in practice it has worked very well for me.)"

From http://www.xpro.com.au/Presentations/UsingCVS/Document%20Version%20Control%20with%20CVS.htm

"By default, CVS uses an optimistic multiple writers approach. Everybody has write permission on a file, and changes are merged as the editors commit their changes to the repository. Changes won’t commit without merging. At first, this protocol appears problematic to most people who haven’t used it. In practice, manual intervention is only required for lines which have been modified by both editors involved in the merge. As with file-locking, this protocol is not without risk. It is possible to introduce logical errors to a file which has merged without incident, as added or deleted lines can change the semantics of the prior version. This technique is most effective when changes are committed frequently and the number of simultaneous writers is minimised."

About Scott

Scott Hanselman is a former professor, former Chief Architect in finance, now speaker, consultant, father, diabetic, and Microsoft employee. He is a failed stand-up comic, a cornrower, and a book author.

About Newsletter

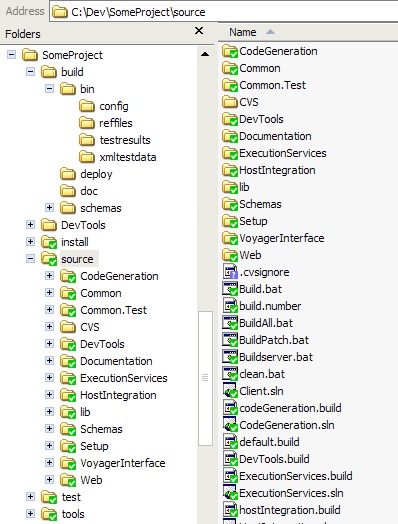

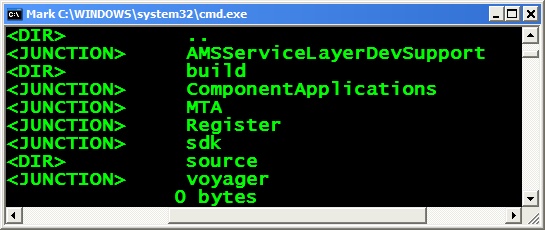

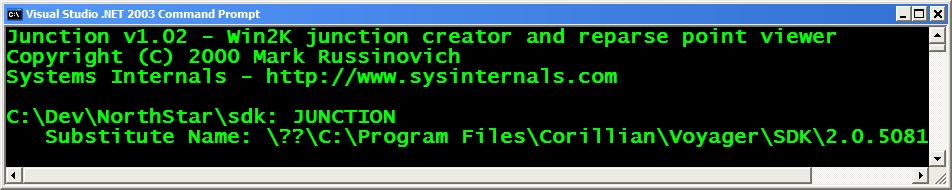

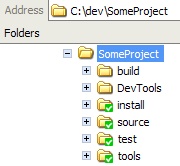

How do we organize our code? Well, it all depends on the project and what we're trying to accomplish. We're also always learning. Our big C++ app builds differently than our lightweight C# stuff. However, for the most part we start with some basic first principles.

How do we organize our code? Well, it all depends on the project and what we're trying to accomplish. We're also always learning. Our big C++ app builds differently than our lightweight C# stuff. However, for the most part we start with some basic first principles.